Version control

Overview

Teaching: 35 min

Exercises: 0 minQuestions

How can I record the revision history of my code?

Objectives

Configure

gitthe first time it is used on a computer.Create a local Git repository.

Go through the modify-add-commit cycle for one or more files.

Explain what the HEAD of a repository is and how to use it.

Identify and use Git commit numbers.

Compare various versions of tracked files.

Restore old versions of files.

Follow along

For this lesson participants follow along command by command, rather than observing and then completing challenges afterwards.

What is version control?

A version control system stores a main copy of your code in a repository, which you can’t edit directly.

Instead, you checkout a working copy of the code, edit that code, then commit changes back to the repository.

In this way, the system records a complete revision history (i.e. of every commit), so that you can retrieve and compare previous versions at any time.

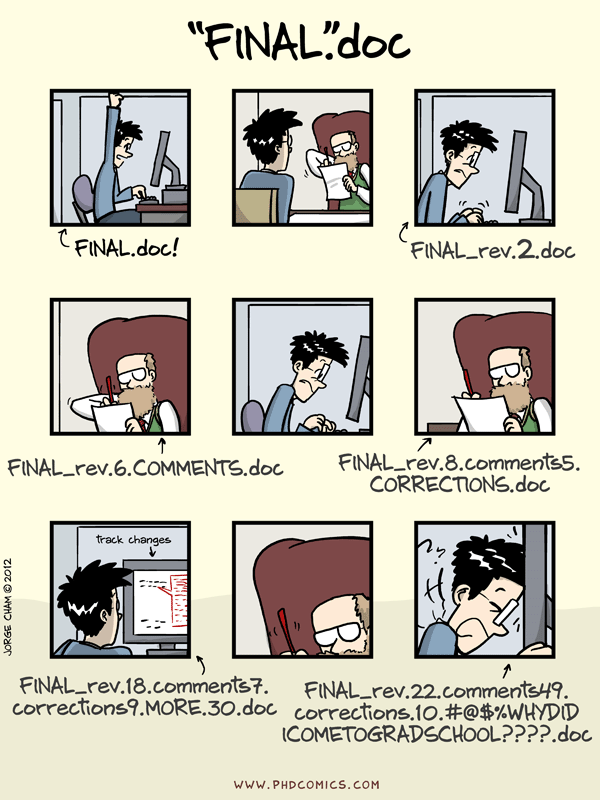

This is useful from an individual viewpoint, because you don’t need to store multiple (but slightly different) copies of the same script.

“Piled Higher and Deeper” by Jorge Cham, http://www.phdcomics.com

It’s also useful from a collaboration viewpoint (including collaborating with yourself across different computers) because the system keeps a record of who made what changes and when.

What is Git?

- git is software that lets you work on a set of files without losing track of previous versions of those files

- git enables multiple people to work on the same set of files simultaneously

- git keeps track of changes in a repository so that they

- won’t be lost

- they can be shared

- git is one of several tools for revision control, also known as version control

What is Github?

We will delve into github a bit more in the next lesson.

- GitHub is a free* website that makes it easier to use git.

- GitHub facilitates creating, browsing, and sharing git repositories

- GitHub provides tools that complement git, such as software licensing, issue tracking, wikis, and various kinds of automation

- GitHub includes visualizations that help you understand your version history such as side by side views of changed versions with differences color-coded.

- GitHub is one of the largest collections of open-source software in the world

- GitHub is one of several websites and/or tools that work with git; Others include Bitbucket and GitLab

Frequently Asked Questions

- Is git just for code?

- No, but you should generally only use it for small text files (small = <1MB) because it’s designed and optimized for code.

- Can I use git with my favorite programming tools?

- Yes

- Is git hard to learn?

- Yes and no. Commands are simple, concepts can be tricky at first.

- Is GitHub just for open-source software?

- No, you can use it for copyrighted software and you can create private repositories

- Can I use git without using GitHub?

- Yes

- Is github free?

- Yes, the core functionality of github is free though there are some limitations such as the number of collaborators in a private repository. There is no longer a limit to the number of private repositories you create in a free account.

More resources

- Git and GitHub tutorial by Joe Futrelle, WHOI IS App Dev, 19 June 2020

- Disclaimer: Github continues to update how the site looks and add new features. Some of the screenshots may look different now. Special thanks to Joe for allowing us to pull content from his workshop for this lesson.

- link to slides

- link to recording

- Software Carpentry: Version Control with Git

- Git cheat sheet

Setup to work with Git locally on your computer

It is possible to use github.com alone to manage your version control, but we are going to show you how to use Git locally to work with files on your computer. This will help demonstrate the foundational concepts of git and make what you see in github clearer.

When we use Git on a new computer for the first time, we need to configure a few things.

We recommend following along with “Git Bash” application for Windows and Terminal (Linux/Mac).

$ git config --global user.name "Your Name"

$ git config --global user.email "you@email.com"

This user name and email will be associated with your subsequent Git activity, which means that any changes pushed to GitHub, BitBucket, GitLab or another Git host server later on in this lesson will include this information.

You only need to run these configuration commands once - git will remember then for next time.

We then need to navigate to our data-carpentry directory

and tell Git to initialise that directory as a Git repository.

$ cd ~/Desktop/data-carpentry

$ git init

If we use ls to show the directory’s contents,

it appears that nothing has changed:

$ ls -F

data/ script_template.py

plot_precipitation_climatology.py

But if we add the -a flag to show everything,

we can see that Git has created a hidden directory within data-carpentry called .git:

$ ls -F -a

./ data/

../ plot_precipitation_climatology.py

.git/ script_template.py

Git stores information about the project in this special sub-directory. If we ever delete it, we will lose the project’s history.

We can check that everything is set up correctly by asking Git to tell us the status of our project:

$ git status

$ git status

On branch master

Initial commit

Untracked files:

(use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

data/

plot_precipitation_climatology.py

script_template.py

nothing added to commit but untracked files present (use "git add" to track)

Tracking changes

The “untracked files” message means that there’s a file/s in the directory

that Git isn’t keeping track of.

We can tell Git to track a file using git add:

$ git add plot_precipitation_climatology.py

and then check that the right thing happened:

$ git status

On branch master

Initial commit

Changes to be committed:

(use "git rm --cached <file>..." to unstage)

new file: plot_precipitation_climatology.py

Untracked files:

(use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

data/

script_template.py

Git now knows that it’s supposed to keep track of plot_precipitation_climatology.py,

but it hasn’t recorded these changes as a commit yet.

To get it to do that,

we need to run one more command:

$ git commit -m "Initial commit of precip climatology script"

[master (root-commit) 32b1b66] Initial commit of precip climatology script

1 file changed, 121 insertions(+)

create mode 100644 plot_precipitation_climatology.py

When we run git commit,

Git takes everything we have told it to save by using git add

and stores a copy permanently inside the special .git directory.

This permanent copy is called a commit (or revision)

and its short identifier is 32b1b66

(Your commit may have another identifier.)

We use the -m flag (for “message”)

to record a short, descriptive, and specific comment that will help us remember later on what we did and why.

If we just run git commit without the -m option,

Git will launch nano (or whatever other editor we configured as core.editor)

so that we can write a longer message.

If we run git status now:

$ git status

On branch master

Untracked files:

(use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

data/

script_template.py

nothing added to commit but untracked files present (use "git add" to track)

it tells us everything is up to date.

If we want to know what we’ve done recently,

we can ask Git to show us the project’s history using git log:

$ git log

commit 32b1b664a647abbbe46a12ce98b25fa2cbbb7c76

Author: Damien Irving <my@email.com>

Date: Mon Dec 18 14:30:16 2017 +1100

Initial commit of precip climatology script

git log lists all commits made to a repository in reverse chronological order.

The listing for each commit includes

the commit’s full identifier

(which starts with the same characters as

the short identifier printed by the git commit command earlier),

the commit’s author,

when it was created,

and the log message Git was given when the commit was created.

Let’s go ahead and open our favourite text editor and

make a small change to plot_precipitation_climatology.py

by editing the description variable

(which is used by argparse in the help information it displays at the command line).

description='Plot the precipitation climatology for a given season.'

When we run git status now,

it tells us that a file it already knows about has been modified:

$ git status

On branch master

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git checkout -- <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

modified: plot_precipitation_climatology.py

Untracked files:

(use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

data/

script_template.py

no changes added to commit (use "git add" and/or "git commit -a")

The last line is the key phrase:

“no changes added to commit”.

We have changed this file,

but we haven’t told Git we will want to save those changes

(which we do with git add)

nor have we saved them (which we do with git commit).

So let’s do that now. It is good practice to always review

our changes before saving them. We do this using git diff.

This shows us the differences between the current state

of the file and the most recently saved version:

$ git diff

$ git diff

diff --git a/plot_precipitation_climatology.py b/plot_precipitation_climatology.

index 056b433..a0aa9e4 100644

--- a/plot_precipitation_climatology.py

+++ b/plot_precipitation_climatology.py

@@ -99,7 +99,7 @@ def main(inargs):

if __name__ == '__main__':

- description='Plot the precipitation climatology.'

+ description='Plot the precipitation climatology for a given season.'

parser = argparse.ArgumentParser(description=description)

parser.add_argument("pr_file", type=str,

The output is cryptic because

it is actually a series of commands for tools like editors and patch

telling them how to reconstruct one file given the other.

If we break it down into pieces:

- The first line tells us that Git is producing output similar to the Unix

diffcommand comparing the old and new versions of the file. - The second line tells exactly which versions of the file

Git is comparing;

056b433anda0aa9e4are unique computer-generated labels for those versions. - The third and fourth lines once again show the name of the file being changed.

- The remaining lines are the most interesting, they show us the actual differences

and the lines on which they occur.

In particular,

the

+marker in the first column shows where we added a line.

After reviewing our change, it’s time to commit it:

$ git commit -m "Small improvement to help information"

On branch master

Changes not staged for commit:

modified: plot_precipitation_climatology.py

Untracked files:

data/

script_template.py

no changes added to commit

Whoops:

Git won’t commit because we didn’t use git add first.

Let’s fix that:

$ git add plot_precipitation_climatology.py

$ git commit -m "Small improvement to help information"

[master 444c3c0] Small improvement to help information

1 file changed, 1 insertion(+), 1 deletion(-)

Git insists that we add files to the set we want to commit

before actually committing anything. This allows us to commit our

changes in stages and capture changes in logical portions rather than

only large batches.

For example,

suppose we’re writing our thesis using LaTeX

(the plain text .tex files can be tracked using Git)

and we add a few citations

to the introduction chapter.

We might want to commit those additions to our introduction.tex file

but not commit the work we’re doing on the conclusion.tex file

(which we haven’t finished yet).

To allow for this, Git has a special staging area where it keeps track of things that have been added to the current changeset but not yet committed.

Staging Area

If you think of Git as taking snapshots of changes over the life of a project,

git addspecifies what will go in a snapshot (putting things in the staging area), andgit committhen actually takes the snapshot, and makes a permanent record of it (as a commit). If you don’t have anything staged when you typegit commit, Git will prompt you to usegit commit -aorgit commit --all, which is kind of like gathering everyone for the picture! However, it’s almost always better to explicitly add things to the staging area, because you might commit changes you forgot you made. (Going back to snapshots, you might get the extra with incomplete makeup walking on the stage for the snapshot because you used-a!) Try to stage things manually, or you might find yourself searching for “git undo commit” more than you would like!

Let’s do the whole edit-add-commit process one more time to watch as our changes to a file move from our editor to the staging area and into long-term storage. First, we’ll tweak the section of the script that imports all the libraries we need, by putting them in the order suggested by the PEP 8 - Style Guide for Python Code (standard library imports, related third party imports, then local application/library specific imports):

import argparse

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import xarray as xr

import cartopy.crs as ccrs

import cmocean

$ git diff

diff --git a/plot_precipitation_climatology.py b/plot_precipitation_climatology.

index a0aa9e4..29a40fb 100644

--- a/plot_precipitation_climatology.py

+++ b/plot_precipitation_climatology.py

@@ -1,13 +1,12 @@

import argparse

+

+import numpy as np

+import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import xarray as xr

-import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import cmocean

-import numpy as np

Let’s save our changes:

$ git add plot_precipitation_climatology.py

$ git commit -m "Ordered imports according to PEP 8"

[master f9fb238] Ordered imports according to PEP 8

1 file changed, 2 insertions(+), 2 deletions(-)

check our status:

$ git status

On branch master

Untracked files:

(use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

data/

script_template.py

nothing added to commit but untracked files present (use "git add" to track)

and look at the history of what we’ve done so far:

$ git log

commit f9fb2388a096a217aa2c9e4695bf786605b946c9

Author: Damien Irving <my@email.com>

Date: Mon Dec 18 15:43:17 2017 +1100

Ordered imports according to PEP 8

commit 444c3c045dc69a323e40d4a04813b88e4b89e05e

Author: Damien Irving <my@email.com>

Date: Mon Dec 18 14:59:47 2017 +1100

Small improvement to help information

commit 32b1b664a647abbbe46a12ce98b25fa2cbbb7c76

Author: Damien Irving <my@email.com>

Date: Mon Dec 18 14:30:16 2017 +1100

Initial commit of precip climatology script

Exploring history

Viewing changes between versions is part of git functionality. However, for large changes it can be easier to understand what is going on when looking at them in github. We will get to that in the next lesson, but here is how you can do it on command line with git.

As we saw earlier, we can refer to commits by their identifiers.

You can refer to the most recent commit of the working

directory by using the identifier HEAD.

To demonstrate how to use HEAD,

let’s make a trival change to plot_precipitation_climatology.py

by inserting a comment.

# A random comment

Now, let’s see what we get.

$ git diff HEAD plot_precipitation_climatology.py

diff --git a/plot_precipitation_climatology.py b/plot_precipitation_climatology.

index 29a40fb..344a34e 100644

--- a/plot_precipitation_climatology.py

+++ b/plot_precipitation_climatology.py

@@ -9,6 +9,7 @@ import iris.coord_categorisation

import cmocean

+# A random comment

def convert_pr_units(darray):

"""Convert kg m-2 s-1 to mm day-1.

which is the same as what you would get if you leave out HEAD (try it).

The real goodness in all this is when you can refer to previous commits.

We do that by adding ~1 to refer to the commit one before HEAD.

$ git diff HEAD~1 plot_precipitation_climatology.py

If we want to see the differences between older commits we can use git diff

again, but with the notation HEAD~2, HEAD~3, and so on, to refer to them.

We could also use git show which shows us what changes we made at an older commit

as well as the commit message,

rather than the differences between a commit and our working directory.

$ git show HEAD~1 plot_precipitation_climatology.py

commit 444c3c045dc69a323e40d4a04813b88e4b89e05e

Author: Damien Irving <my@email.com>

Date: Mon Dec 18 14:59:47 2017 +1100

Small improvement to help information

diff --git a/plot_precipitation_climatology.py b/plot_precipitation_climatology.py

index 056b433..a0aa9e4 100644

--- a/plot_precipitation_climatology.py

+++ b/plot_precipitation_climatology.py

@@ -99,7 +99,7 @@ def main(inargs):

if __name__ == '__main__':

- description='Plot the precipitation climatology.'

+ description='Plot the precipitation climatology for a given season.'

parser = argparse.ArgumentParser(description=description)

parser.add_argument("pr_file", type=str,

We can also refer to commits using

those long strings of digits and letters

that git log displays.

These are unique IDs for the changes,

and “unique” really does mean unique:

every change to any set of files on any computer

has a unique 40-character identifier.

Our second commit was given the ID

444c3c045dc69a323e40d4a04813b88e4b89e05e,

but you only have to use the first seven characters

for git to know what you mean:

$ git diff 444c3c0 plot_precipitation_climatology.py

commit 444c3c045dc69a323e40d4a04813b88e4b89e05e

Author: Damien Irving <my@email.com>

Date: Mon Dec 18 14:59:47 2017 +1100

Small improvement to help information

diff --git a/plot_precipitation_climatology.py b/plot_precipitation_climatology.py

index 056b433..a0aa9e4 100644

--- a/plot_precipitation_climatology.py

+++ b/plot_precipitation_climatology.py

@@ -99,7 +99,7 @@ def main(inargs):

if __name__ == '__main__':

- description='Plot the precipitation climatology.'

+ description='Plot the precipitation climatology for a given season.'

parser = argparse.ArgumentParser(description=description)

parser.add_argument("pr_file", type=str,

Recovering/Reverting

All right! So we can save changes to files and see what we’ve changed—now how can we restore older versions of things? Let’s suppose we accidentally overwrite our file:

$ echo "whoops" > plot_precipitation_climatology.py

$ cat plot_precipitation_climatology.py

whoops

git status now tells us that the file has been changed,

but those changes haven’t been staged:

$ git status

On branch master

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git checkout -- <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

modified: plot_precipitation_climatology.py

Untracked files:

(use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

data/

script_template.py

no changes added to commit (use "git add" and/or "git commit -a")

We can put things back the way they were at the time of our last commit

by using git checkout:

$ git checkout HEAD plot_precipitation_climatology.py

$ cat plot_precipitation_climatology

import argparse

import numpy

...

As you might guess from its name,

git checkout checks out (i.e., restores) an old version of a file.

In this case,

we’re telling Git that we want to recover the version of the file recorded in HEAD,

which is the last saved commit.

We’ve lost the random comment that we inserted (that change hadn’t been committed) but everything else is there.

plot_precipitation_climatology.py

At the conclusion of this lesson your

plot_precipitation_climatology.pyscript should look something like the following:import argparse import numpy as np import matplotlib.pyplot as plt import xarray as xr import cartopy.crs as ccrs import cmocean def convert_pr_units(darray): """Convert kg m-2 s-1 to mm day-1. Args: darray (xarray.DataArray): Precipitation data """ darray.data = darray.data * 86400 darray.attrs['units'] = 'mm/day' return darray def create_plot(clim, model_name, season, gridlines=False, levels=None): """Plot the precipitation climatology. Args: clim (xarray.DataArray): Precipitation climatology data model_name (str): Name of the climate model season (str): Season Kwargs: gridlines (bool): Select whether to plot gridlines levels (list): Tick marks on the colorbar """ if not levels: levels = np.arange(0, 13.5, 1.5) fig = plt.figure(figsize=[12,5]) ax = fig.add_subplot(111, projection=ccrs.PlateCarree(central_longitude=180)) clim.sel(season=season).plot.contourf(ax=ax, levels=levels, extend='max', transform=ccrs.PlateCarree(), cbar_kwargs={'label': clim.units}, cmap=cmocean.cm.haline_r) ax.coastlines() if gridlines: plt.gca().gridlines() title = '%s precipitation climatology (%s)' %(model_name, season) plt.title(title) def main(inargs): """Run the program.""" dset = xr.open_dataset(inargs.pr_file) clim = dset['pr'].groupby('time.season').mean('time') clim = convert_pr_units(clim) create_plot(clim, dset.attrs['model_id'], inargs.season, gridlines=inargs.gridlines, levels=inargs.cbar_levels) plt.savefig(inargs.output_file, dpi=200) if __name__ == '__main__': description='Plot the precipitation climatology for a given season.' parser = argparse.ArgumentParser(description=description) parser.add_argument("pr_file", type=str, help="Precipitation data file") parser.add_argument("season", type=str, help="Season to plot") parser.add_argument("output_file", type=str, help="Output file name") parser.add_argument("--gridlines", action="store_true", default=False, help="Include gridlines on the plot") parser.add_argument("--cbar_levels", type=float, nargs='*', default=None, help='list of levels / tick marks to appear on the colorbar') args = parser.parse_args() main(args)

Key Points

Use git config to configure a user name, email address, editor, and other preferences once per machine.

git initinitializes a repository.

git statusshows the status of a repository.Files can be stored in a project’s working directory (which users see), the staging area (where the next commit is being built up) and the local repository (where commits are permanently recorded).

git addputs files in the staging area.

git commitsaves the staged content as a new commit in the local repository.Always write a log message when committing changes.

git diffdisplays differences between commits.

git checkoutrecovers old versions of files.